Naum Gabo — Constructions for Real Life exhibition

Tate St. Ives

Great artists present a challenge to the status quo that moves beyond aesthetics and confront us with insight. Naum Gabo’s (1890 –1977) insights are set out in The Realist Manifesto from 1920. He declares that art should drive social change, incorporate the latest technology, be contemporary and available to everyone. He was an early pioneer of constructivismand collaborated with the modernist movement whilst at the Bauhaus.

“Art is called upon to accompany man everywhere where his tireless life takes place and acts: at the workbench, at the office, at work, at rest, and at leisure; work days and holidays, at home and on the road, so that the flame of life does not go out in man.”

The Realistic Manifesto, 1920.

Gabo’s sculptures are kinetic exercises in modernity that demand art and architecture incorporate science and technology. His sculptures aren’t concerned with defining mass or volume, instead they explore space through light and perspective.

Much of his work exhibits a lightness that’s not related to scale, but is a reflection of the materials chosen to reveal space. Through the use of transparent plastics and glass, solid planes become ethereal. Intricate steel and nylon threads wind asymmetrically between planes to define form and depth without the use of solid lines.

The weightlessness of these forms is in contrast to the tensile forces bound by each wire. Each thread suggests a different space as you move around the sculpture, allowing perspective to define new dimensions.

“The line is only an accidental trace that humans leave on objects.”

The Realistic Manifesto, 1920.

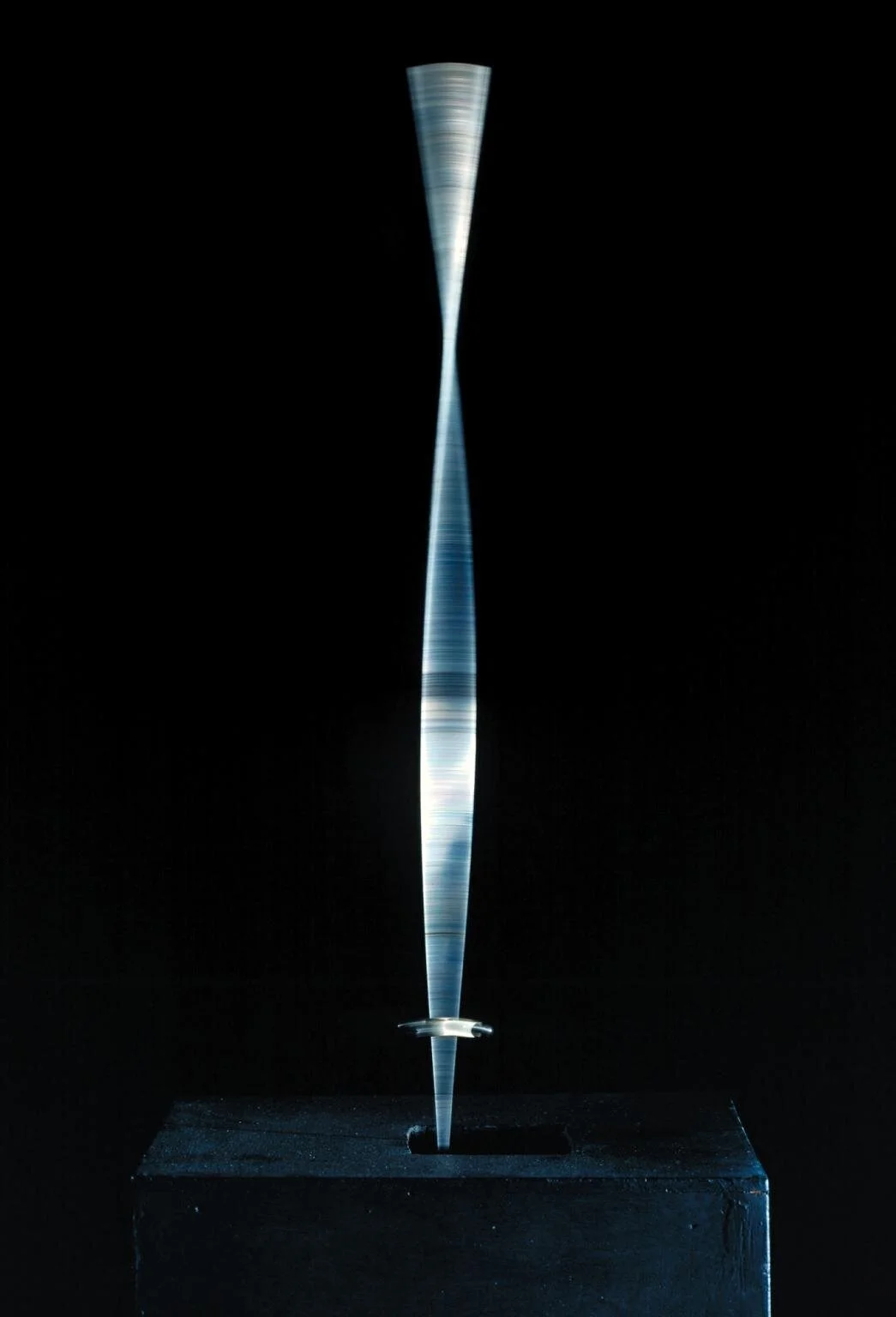

Dimension is a recurring theme in Gabo’s work. The Realistic Manifesto asks us to consider all dimensions humans can perceive, which Gabo explores in his kinetic sculptures like Standing Wave. The push of a button starts the oscillation of a steel rod to create the illusion of an organic twisting structure.

Alongside sculptures and models, on exhibition are architectural drawings, sketches and paintings. Gabo envisions transparent towers that reveal their occupants, allowing the movement of people to define dimension without prescribing volume. His designs for enormous public monuments and utopian optimism are reflective of Gabo’s belief in the power of art, design and architecture to push society forward to a more enlightened age. Even these futuristic concepts are grounded in Gabo’s definition of the real as he imagines the potential of contemporary materials to realise his concepts.

Throughout Gabo’s work there is a rejection of the classical in search for innovation that’s grounded in technological discovery; little reverence is shown for art movements that abstract from the reality of lived experience such as cubism or surrealism. The Realistic Manifesto rejects the decorative use of colour, line and stasis, claiming they fail to reveal the true forms and rhythms that Gabo perceived as the real.

“And we do not measure our work by the yardstick of beauty, we do not weigh it on the scales of tenderness and feeling. The plumb line in hand, the look accurate as a ruler, the mind rigid as a compass, we are building our works as the universe builds. This is why, when we represent objects, we are tearing up the labels their owners gave them, everything that is accidental and local, leaving them with just their essence and their permanence, to bring out the rhythm of the forces that hide in them.”

The Realistic Manifesto, 1920.