The guilt of not being a UX designer

Why I feel guilty

For the last six years I’ve felt so guilty about not being a UX designer, I almost left the design profession.

The guilt started when I was working in advertising and branding. When you’re selling products to people that they don’t really need, you wonder if what you’re doing is of any value to the world. I’ve spent most of my career working in retail for companies that have exhibited some dubious and predatory behaviour, that although offered incredible opportunities for me as a creative, never left me feeling fulfilled or great about what I do for a living.

Then UX design came along and I felt guilty for whole new reasons.

To me, it appeared that people working in UX were building the technologies and software that define the future. More than that, UX designers were able to effectively measure the efficacy of their designs, learn what they could do better and then implement solutions in a way that a campaign for protein powder could only dream of.

But I’m not a UX designer — or at least I don’t identify as one. So now I worry I’m being left behind professionally. I feel guilty that I’m not a part of where the industry is heading. That I might lose my job. That my skillset is no longer valuable.

I feel scared that hundreds of people enter the industry every week after doing an online bootcamp in UX and might be more employable than me because of their templated cases studies and better SEO.

I feel guilty when wondering if I’m failing my family by not doubling down on the most profitable part of my skillset.

How did we get here?

When the industry realised the internet was the platform of the future, it felt like everyone updated their CV overnight from ‘graphic designer’ to ‘web designer’. I think that upheaval prepared the industry for the next big pivot — the professionalisation of a specific role for user experience design, and more recently, digital product design.

Design education trains us to identify as problem solvers. For most of the 20th century, the problems designers most often solved were branding and advertising. We were concerned with how people think and feel about a brand, product or service.

How do you estimate the financial value of a logo to a company? Or the effectiveness of billboard advertising versus print or TV? It’s a nuanced and often intangible value to measure. Some companies accept the investment in their brand is unquantifiable and others demand to know how much sales uplift the new packaging you’ve designed will provide to two significant figures.

UX on the other hand, that’s an easy sell. Ever since Eric Ries published The Lean Startup and coined the term ‘Minimum Viable Product’, the value of data informed design has been ingrained in the startup playbook. We stopped designing solutions in their entirety before releasing them to the world and started to release specific features to users in order to validate hypotheses about their behaviours, wants and needs. It was like business had a new silver bullet to solve all their problems.

We can attach both quantitive and qualitative data to prove ROI when it comes to user experience design. We can get buy in from the upper echelons of a company through ownership of strategy, product roadmaps and KPI’s. We can present to board members real data that shows how the new checkout user journey we’ve designed has increased conversions by 2%.

Try asking the same board members for £15000 to shoot a Christmas campaign when they could spend the same budget on stock photography and social ads.

A cycle begins that can alienate any creative who isn’t a fully signed up member of the UX clan. Whereas UX designers can more readily converse in the language of executives through KPI’s and quantitative metrics, creatives focused on brand and advertising can be interpreted as missing the critical faculties to be part of these discussions when they reference qualitative factors like how people feel about design.

This position can be legitimised as UX designers tend to make more money than their colleagues in more traditional practices. Currently, demand for UX designers far outstrips supply so wages are inflated to attract talent. It’s not a huge stretch to imagine how a more expensive resource can have more value attached to their opinion.

I’ve felt the pressure build to formalise the entirety of the design profession into a purely quantitative results generating machine because our less tangible output is compared directly to our colleagues more rationalised outcomes. In a similar way to how sociology moved more towards qualitative research to legitimise the profession as a social science in comparison to economics.

Further pressure has been applied by the democratisation of technology that allows anyone in the world to be a designer. There are websites like Fiverr, where you can literally get a logo for £5; Brandmark, which uses machine learning to generate hundreds of logo variants in browser and even Squarespace has a self-serve logo making platform.

These kinds of platforms have forced prices down for many creative services, even if they only offer solutions to the most superficial aspects of brand. Clients rightly ask, ‘why should I pay you thousands for a logo when I can get one for a fiver?’ Of course the best branding agencies in the world have exceptional answers and value creation to answer that question, but for in-house graphic designers there’s always a looming threat of being replaced by cheaper technology.

Why I don’t identify as a UX designer

Try and get one answer about what UX design actually is. Chances are that you’ll find the viral LinkedIn meme below.

In small companies, a UX designer could be doing user research, making prototypes and creating UI within the same day. Larger organisations tend to separate these processes into discreet specialised roles. A large UX team can include researchers, writers, testers, analysts, developers and visual designers.

Either way, the processes are very similar. We empathise and aim to understand a problem from the perspective of the end users and business needs. We define the requirements and scope of how we plan to solve those problems and then design a solution within those parameters.

To me, that’s just design.

I’m not trying to minimise the additional knowledge that comes from specialising in different niches of design. To create good human-computer interactions you need to have knowledge of many things that someone who has only worked in print won’t have.

What makes me angry is the misattribution of where value is being generated. Is a UX designer more valuable than a graphic designer because they know how many pixels deep a button should be on mobile or the pros and cons of using a burger nav? Those are things you can learn with little resistance.

The value of a design professional comes from all the decisions made along the way to create a solution. The consulting, stakeholder management and hand holding it takes to realise a vision. These skills are learned through experience and mentoring, not through ‘10 epic tips to make awesome wireframes.’

Wireframing and creating design systems are not valuable by themselves. They’re processes we go through to build something. Hopefully what has been created, is a coherent experience that is a unique reflection of a brands individual solution to an audiences problem.

That’s why I resisted attaching UX to my job title. Even if when I list out the main aspects of my current job, there’s a lot of overlap with a what a typical UX or product designer will do. I pivoted into a role with less art direction and more digital product design, partly because of the guilt and partly because I was chasing what was in fashion.

I felt a shame attached to being a graphic designer — or more accurately a commercial artist. That all we make are pictures to sell things.

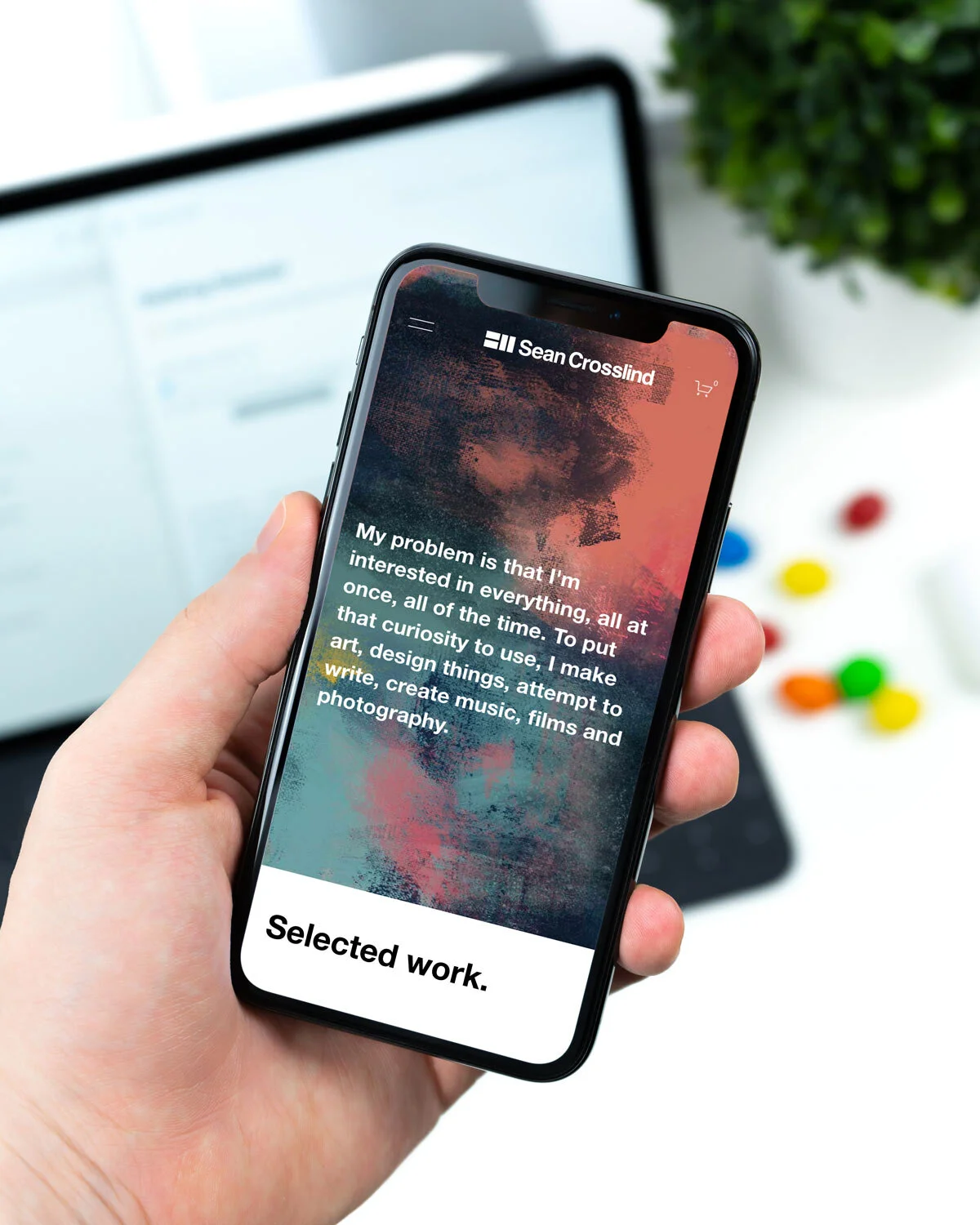

But I couldn’t feel comfortable in my own skin describing myself as a UX designer when I believe that limits what I’m allowed to work on as a creative. I love to art direct, illustrate, work in a photo studio and make beautiful images. It’s hard to go back to that after you’ve added those extra two letters to your CV, even though to me, it’s all the same thing.

My educational background is Architecture. I’m glad I’m not an architect, but I genuinely believe this training makes me different to many other designers. I learnt how to engage with design holistically, to look at the whole, to not objectify a solution. My opinion is that a great designer can make anything. It’s our ability to make sense of competing interests and limitations and turn that into a solution that makes what we do valuable.

“Be it graphic design, typographic design, digital design, user experience design — all great design marries business imperatives with leaps of inspired lateral connections. Design is both commercial and artistic.” — Simon Manchipp

So no, I am not a UX designer. I am a designer.

I’m not going to change my job title again by adding a new noun. 10 years from now, most of the current UX design workflow will be carried out more efficiently by AI. So then we’ll all be AI designers and I can feel guilty that I’m not one of those either.

Fuck it.